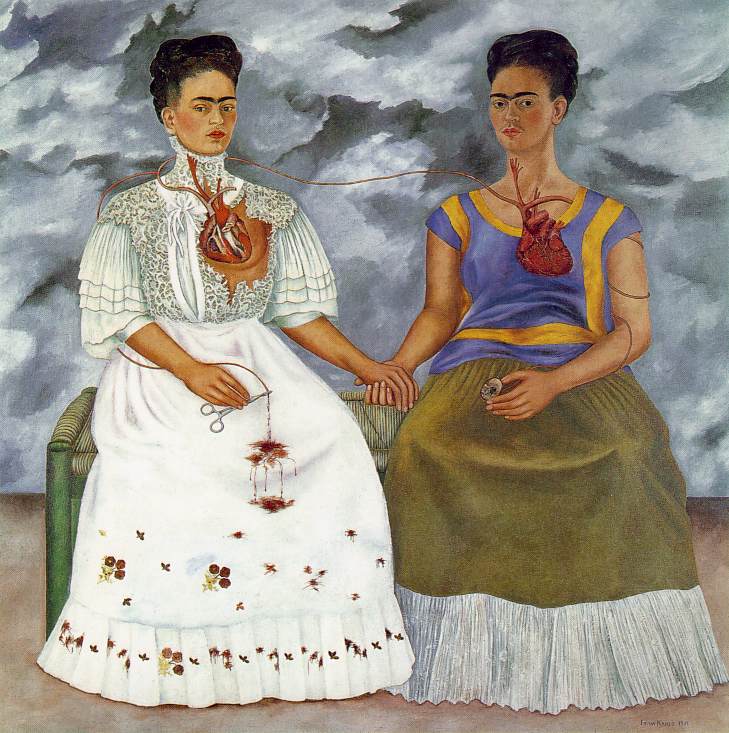

Frida Kahlo was once principally known as the long-suffering wife of philandering Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. But during the half-century since her death her own work as a painter has come to be held in increasingly high regard. In recent years she has become something of a cult figure, revered by her admirers as a kind of early feminist martyr, as well as a pioneering manipulator of her own image – and, by extension, the image of modern woman in general. Her numerous, artfully strange self-portraits are seen to have anticipated the work of such recent influential artists as Cindy Sherman. as well as to have foreshadowed the multiple image-shifts of modern pop stars such Madonna. Partly because of Kahlo’s very popularity among those she has influenced – Madonna collects her work as well as admiring it – a relatively large proportion of her oeuvre remains in private hands. So Tate Modern’s retrospective of her work represents a rare opportunity to assess the nature of her achievement.

Kahlo always had her admirers, although many of them seem to have had a certain amount of difficulty in knowing where to place a painter whose work presented such an unusual hybrid of Mexican folksiness, Old Master references, modernist sophistication and blood-and-guts confession. Picasso reportedly paid her the ambiguous compliment of remarking that no one could paint a head like she did. Andre Breton tried to co-opt her to the Surrealist movement, regarding her as a miraculous manifestation of spontaneous Surrealism sprung straight from the Mexican soil. This was a naïve view, given Kahlo’s evident familiarity with the idioms of European modern art, gleaned partly from magazines and partly from visits to major European cities – and she was, in any case, keen to distance herself from too close an association with Surrealism....

Frida Kahlo at Tate Modern

12-06-2005