Andrew Graham-Dixon on visitors from the Soviet Union

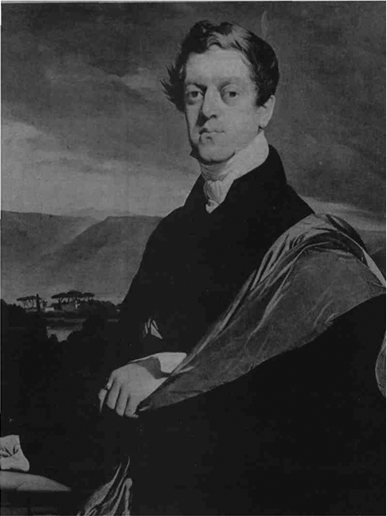

INGRES' portrait of Count Nicolas Dmitrievich de Guryev is a memorable image of boss-eyed aristocratic hauteur. Count Nicolas, his hair tousled romantically by a stiff breeze, clearly knew a thing or two when it came to cutting a dash. If he didn't Ingres, no slouch when it came to making the best of a subject, more than compensated for any awkwardness.

The Count stands, ramrod-like, against a marble balustrade, on which he rests one kid-gloved hand. The background is a stormy Tuscan landscape (the sitter was Russian ambassador to Tuscany in the 1820s), whose blue-tinged mountains are both mirrored and dwarfed by the sitter's soberly clad physique. Ingres' Russian Count is, himself, a precipitous visual climb, a formidable crag rising from that gloved hand up a steep escarpment of arm, levelling briefly at the shoulder, only to rise still more sharply until you reach that imperturbable, cloud-capped visage.

Ingres's portrait, one of 38 "French Paintings from the USSR" currently on view at the National Gallery, is at pains to point out that its subject inhabits a different, higher plane of existence from the rest of us. Its most striking feature is a vivid flash of crimson drapery, the lining of the Count's cloak, which he has flung insouciantly over one shoulder: an effective visual barrier that heightens the Count's distance from the clamouring multitude. You can't help wondering what they must make of Ingres' aristocratic icon in Russia, where this sort of thing went out of fashion, with a vengeance, in 1917.

"French Paintings from the USSR" is part of an exchange which gives the Russians a chance to catch up on the National Gallery's treasures (assorted Ho-garths, Constables, Rembrandts, Titians and other paintings from the National are currently on view over...