THE PAINTER Francis Bacon died yesterday. He was 82.

''I have often thought upon death and I find it the least of all evils,'' wrote Francis Bacon's namesake and ancestor, the Elizabethan philosopher.

For Bacon the painter, the opposite was true. Death was the greatest of evils: ''I have a feeling of mortality all the time,'' he once said. ''Because, if life excites you, its opposite, like a shadow, death, must excite you. Perhaps not excite you, but you are aware of it in the same way as you are aware of life, you are aware of life, you're aware of it like the turn of a coin between life and death . . . I'm always very surprised when I wake up in the morning.''

Mortality was Bacon's great theme, his keen sense of his own mortality the driving force behind his art. His paintings are not pleasant, embodying a singularly bleak view of human existence, but they have a power born of obsession that is unique in British post-war art.

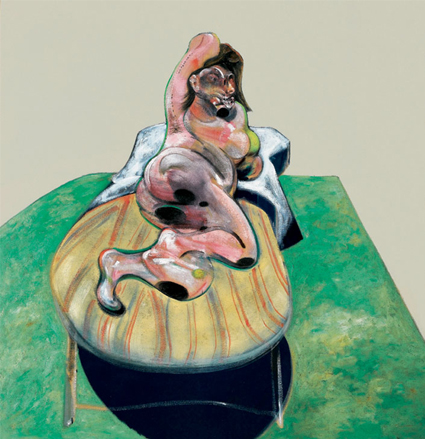

Storyless, enigmatic compositions, characteristically painted in triptych format, they place the emphasis on prime biological fact; figures - usually male - scream, couple bestially, vomit or defecate, depicted as lurid agglomerations of bodily matter, raw flesh that seems on the point of putrefaction. Their beauty is the beauty of rottenness.

''I've always been very moved by pictures about slaughterhouses,'' he said, and Bacon's figures, frequently isolated on the flattest and most uninflected areas of pure colour, almost like clinical specimens, have something of the slaughterhouse about them. ''We are meat, we are potential carcases,'' he said, and painted the fact.

Bacon's place in art history is assured, yet it is also true that art historians have never known quite what to make of him. He distrusted interpretation of...