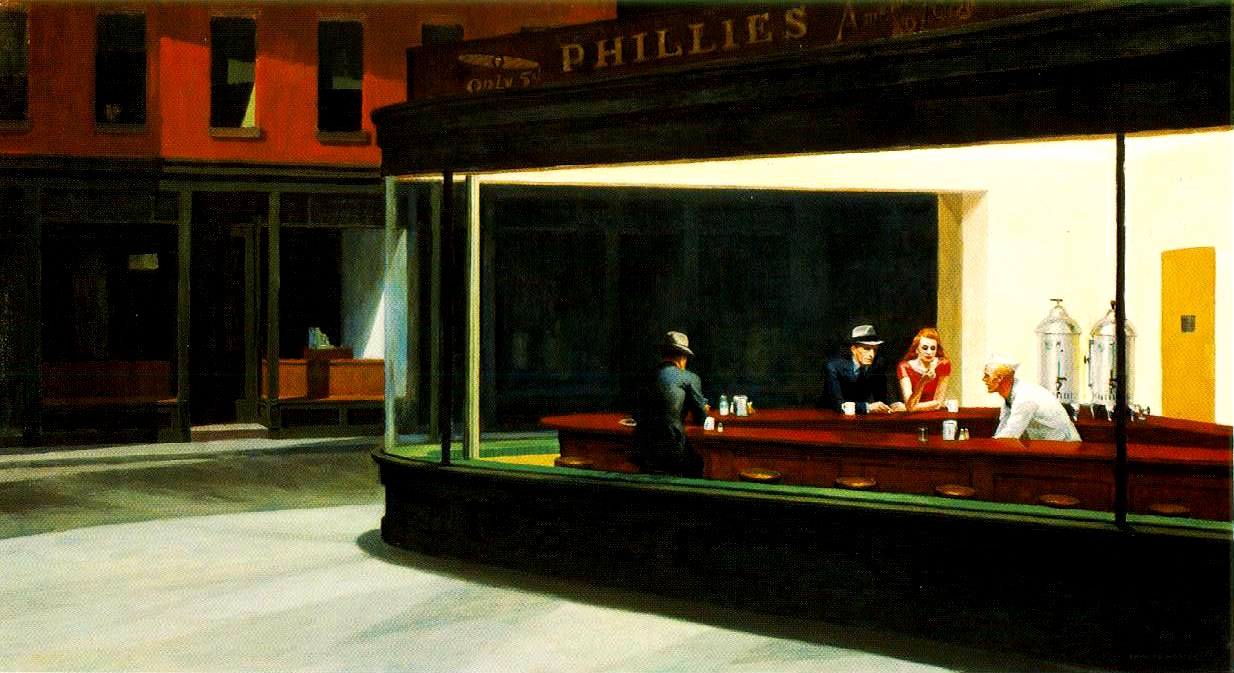

The first painting that confronts visitors to Tate Modern’s Edward Hopper retrospective is a small, greyish work in oils on board entitled Solitary Figure in Theatre. A slice of city life, it shows the silhouette of a man sitting in the front stalls of some unidentifiable playhouse, attempting to read something – a newspaper? a programme? – although the general murk in which he finds himself suggests that the house lights are down. The proscenium-arch stage beyond him frames a monochrome void, painted in layers of grey on grey: a mottled, pulsing emptiness. Hopper was twenty-four years old when he made the picture, and it would be another twenty years before he established himself sufficiently to work full-time as an artist, but here already are ample portents of his future preoccupations. He disliked storytelling, drama or anything smacking too overtly of spectacle, preferring to cultivate the mysteries of the charged non-event. He liked to paint people alone with their thoughts and often contrived to place those people in some kind of void space, sharpening the sense of their isolation. The challenge that faces them is the same challenge that the artist set himself – to find something – some meaning, some glint or glimmer of significance – in nothing much at all.

The son of a dry goods merchant, Hopper was born and brought up in Nyack, New Jersey. Apart from a period of study in Paris in 1906-7, and two brief visits to Europe in 1909 and the following year, he spent almost all of his life in America. He wrote almost jingoistically about the importance of the American artist learning to paint, so to speak, in his own voice, without a trace of French accent, but in truth Hopper never quite managed this himself. In his youth...

Edward Hopper at Tate Modern 2004

30-05-2004