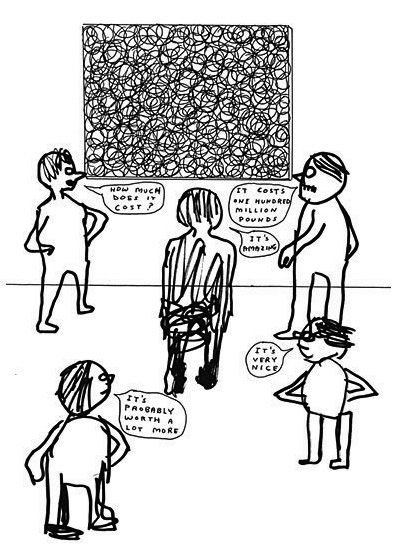

“Drawing is the probity of art,” declared the nineteenth-century French painter Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, staunch upholder of tradition and self-proclaimed last bastion of le pur classique. “Drawing includes three and a half quarters of the content of painting. If I were asked to put a sign above my door it would read ‘School of Drawing’, and I am certain that I would produce painters.” Times have changed in the world of fine art education, to put it mildly. For many centuries, indeed for millennia, to judge by the ancient Roman painters’ motto, “nulla dies sine linea” – never a day without a line – drawing was regarded as the first and most essential skill needed by any artist. But in the age of the unmade bed, the pickled shark and the bust of frozen blood, the practice is widely perceived as an old-fashioned activity – outmoded, fogeyish even.

Drawing has what spin doctors call an image problem. This is compounded by the fact that its most fervent apologists, those who lament the modern artist’s apparently declining standards in draughtsmanship most vocally and melancholically, tend to occupy the extreme right wing of contemporary artistic debate (much as Ingres did, in fact, in mid-nineteenth-century France). The importance of drawing is the sort of thing that Brian Sewell enjoys fulminating about, when he is not busy chastising the panjandrums of Tate Modern for their refusal to allow anyone producing anything resembling traditional painting or sculpture to win the Turner Prize. Drawing is something championed by the likes of the Stuckists, that coterie of neo-traditional artists who proudly took their nom de guerre from the tirade directed against them by Tracey Emin – the gist of which was that they were “stuck, stuck, stuck” in the dead past.

Given the way in...

Drawing

30-11-1999