“Diane Arbus: Revelations”, which opened last week at the Victoria and Albert Museum, is the first retrospective of this brilliant and much misunderstood American photographer’s work to have been seen in this country for more than thirty years. The exhibition contains around two hundred pictures by Arbus, among them some of the most remarkable, poignant and beguilingly weird photographs ever taken. But this is no straightforward celebration. To see those pictures, the viewer must follow a circuitous path – a veritable labyrinth in fact – punctuated by numerous little rooms laid out like pseudo-shrines containing all kinds of flotsam and jetsam washed up on the tides of Arbus’s restless and often troubled life. In this way, the only objects that truly count and truly matter, the photographs themselves, are half-obscured by thickets of biographical remnant: pages from the journals that Arbus kept; letters to and from her friends; contact sheets; appointment books; and other more ghoulishly revealing material besides.

Arbus is famous for having taken photographs of unusual or developmentally arrested individuals – “freaks” was her own generic term for such people – and she has often been typecast as the quintessentially cruel photographer, revelling in the camera’s power to lay bare and parade the deformities of others. There are times when “Diane Arbus: Revelations” looks like an attempt to turn the tables on her, to reveal Arbus herself as a freak or, at best, a merely sad and strange character. The bare bones of her biography – the footloose search for damaged human goods to photograph; the irregular marriage to fellow New Yorker, Allan Arbus, that terminated in divorce; the bathtub suicide with which she ended her life, at the age of 48, in 1972 – are readily moulded to fit such a misconception. Only her pictures give the...

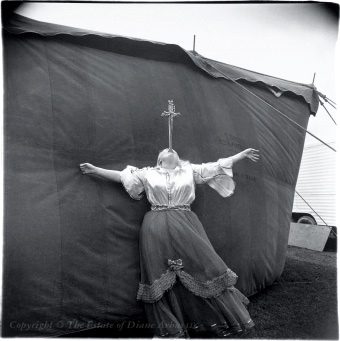

Diane Arbus at the V&A 2005

16-10-2005