Insight into the human condition or personal exorcism? The status of Hans Prinzhorn's collection of art by psychiatric patients is questionable - as is the act of viewing them.

"Madness," declared Socrates, "is a nobler thing than sober sense. Madness comes from God, whereas sober sense is merely human." The ancient notion that insanity might be a form of inspiration has persisted into modern times. During the early Christian period it produced the Holy Fool, blessed by visionary craziness. Shakespeare's King Lear, a secular metamorphosis of that figure, similarly attained a state of higher sanity through going mad. Two hundred years later, the Romantic generation of writers and painters (themselves captivated by Shakespeare's conjuring of extreme mental and emotional states) sought to induce a species of inspired irrationality in themselves by taking opiates. This Romantic transvaluation of insanity reached a peek in the later 19th century, and it is to that period that the origins of a certain modern cult of the lunatic as genius or prophet may be traced.

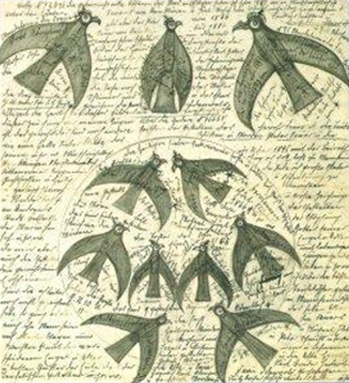

No one developed that cult more systematically and determinedly than Hans Prinzhorn (1866-1933), assistant director of the psychiatric clinic of Heidelberg University, self-styled "Revolutionary on Behalf of Things Eternal" and author of a briefly celebrated book, published in 1922, Artistry of the Mentally Ill. It was Prinzhorn's somewhat grandiose belief that, by studying the art of those suffering from severe mental disturbance, he might gain "a universal overview of all artistic manifestations on this minute terrestrial globe of ours". In his quest to discover the Psychological Foundations of Pictorial Configuration (his capitalisation), he amassed a collection of more than 5,000 paintings, drawings and other objects created by patients from psychiatric hospitals across Europe. That collection still survives, and a selection of some 200 works from it forms "Beyond Reason:...