The Hayward Gallery's ''The Art of Ancient Mexico'' quickly establishes itself as one of the better hung exhibitions in London at the moment. Six fertility goddesses on tall plinths preside sternly over the opening gallery, which also includes a 3ft-long stone phallus from the Museo Nacional de Antropologia in Mexico City. This daunting object was discovered a century ago in the plaza of a small Mexican town called Yahualica, where it played its part in an archaic local custom said to have involved a lot of flowers and a complicated fertility dance.

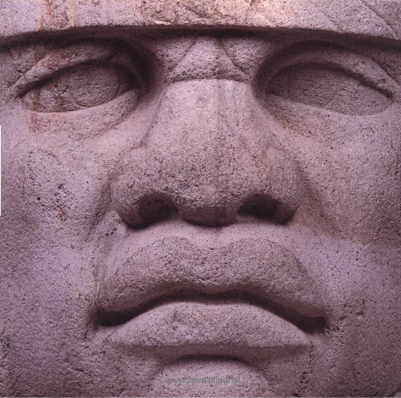

The installation at the Hayward discourages ritual dancing as a response. Labelled exhibit 81, the spotlit phallus is perched on a high ledge beside a snarling Olmec Humanised Jaguar and other relics of ancient Mexican votive cults. It is an unlikely survivor of the Spanish conquest. The evangelists who set out to convert the Mexicans to Christianity did not look too kindly on penis-worship, so most of these stone phalluses were broken up and replaced by Catholic cult objects: statues of the Virgin and the like. Talk about going from one extreme to the other.

But preserving things can itself be a subtle way of destroying them, or at least of denaturing them. Confiscated from the people of Yahualica by 19th-century anthropologists, placed in a museum and now on loan to the Hayward Gallery, Phallic Sculpture exists, these days, to be admired as art. One form of reverence has turned into another. Quite what this transformation has done to the object remains arguable. It makes the Hayward show fertile ground for debate.

To see an exhibition of ancient Mexican sculptures in a modern art gallery is, it might be said, to see them doubly distorted. For one thing, it is to be tempted to see...

Conference of strange deities

09-09-1992