Andrew Graham-Dixon on the garener's cultivated pleasures

THE BRITISH have always preferred horticulture to culture. In the eighteenth cen-tury, Horace Walpole praised the land-scape gardener William Kent for his ability to see that "all nature was a garden", but Sir Joshua Reynolds was closer to the mark when he commented dryly that "gardening, as far as gardening is an art, is a deviation from nature".

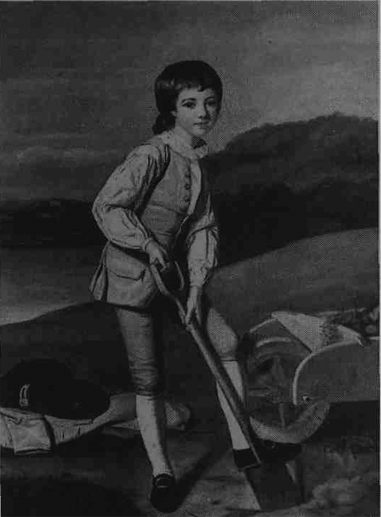

The Glory of the Garden, a splendidly eccentric exhibition which (like the Arts Council's regional funding policy) takes its title from Kipling's poem, is — on one level at least — a fascinating history of the British garden told in topographical paintings, garden plans, and assorted relics from our horticultural past. It is a pleasant combina¬tion of fine art and curios.

We are accustomed to think of the garden as a private refuge, a suburban retreat from the cares of the world. But historically the great garden was a public statement, a declaration of territorial conquest and po¬litical power. Until the early eighteenth century, aristocrats commissioned bird's-eye view paintings of their houses and the rigidly formal gardens that radiated out¬ward from them, in straight lines like the spokes of a wheel.

This show contains one of the masterpieces of British topographical painting, an anonymous seventeenth-century view of the house and gardens at Lianerch which has not been publicly shown for more than a hundred years. Aerial perspective suited the map-like configurations of the formal garden, which declared man's rule over na¬ture by turning it into geometry.

Later — manifest in Rysbrack's and Lambert's views of the Earl of Burlington's Chiswick House, in Capability Brown's gar¬den plans and in the projects of another great landscape gardener, Humphrey Repton — the garden exercised its control over nature by turning it into an outdoor picture gallery, a series...