Andrew Graham-Dixon on the Degas exhibition in Paris

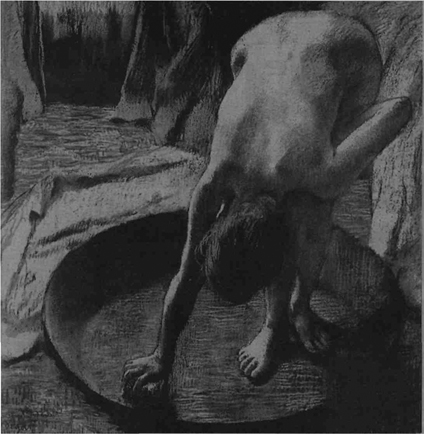

THE MASSIVE Degas exhibition at the Grand Palais rescues a great, revolutionary artist from the coffee-tables of the world. Today, it is perhaps harder than ever to appreciate Degas' radical revisions of the art of his time: his multiple reinventions of painting, his redefinition of ways of seeing. Degas has been perpetually misunderstood as a rather charm¬ing portraitist and genre painter — a petit maître who recorded days at the races, café-concerts, nudes at their toilette and ballet dancers, cute in tutus.

Take a typical, earlyish Degas, his 1865 La Femme aux Chrysanthèmes. At first sight it seems an innocuous, if extremely pleasing, picture. At its centre you see a virtuoso, brushily executed still life of a vase of flowers, standing on a table in what is evidently a bourgeois interior. To its left you notice a pair of gloves and a jug of water; to the right a young woman, half cropped by the picture's edge, leans one elbow on the table and stares out to the side.

Simple enough. But, in the context of art in Paris in the mid-1860s, this is a highly unusual painting. Degas has collapsed the old, generic categories of art and produced an image that defies classification. It is not, strictly, speaking, a still life: the enigmatic presence of the woman (whose expression, on close examina-tion, seems tense, nervous) sees to that. It is not a portrait: what portrait painter, at the time, would have pushed his sitter so far to one side of the frame? It is not a narrative painting, in any conventional sense: there is no anecdote, no moral to be extracted from it, no hint as to what this woman is doing here.

Degas' picture breaks down the old orders of...