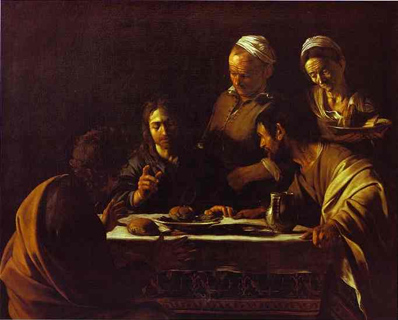

Michelangelo Merisi, usually known as Caravaggio after his birthplace, a village near Milan, only made one recorded statement about painting during the course of his short and turbulent life. “In painting,” he said, “a man of worth is he who knows how to paint well and imitate natural objects well.” It is a provocatively brief remark, which was wrung out of the painter, like blood out of a stone, by a tribunal investigating him on charges of criminal libel. Forced from him as it was, still it rings true as an expression of the painter’s obdurate pride in his Lombard origins. Artists from Milan and thereabouts were associated with a powerful strain of no-nonsense realism – none more so than Caravaggio, whose ability to “imitate natural objects”, and to do so more than merely “well”, had won him some of the most prestigious commissions, despite cut-throat competition, in Rome at the start of the seventeenth century.

The National Gallery’s new exhibition, “Caravaggio: The Later Years”, is an utterly compelling, once-in-a-lifetime experience. A profoundly moving and beautifully installed show, it consists of just sixteen extraordinary pictures, each isolated in its own pool of light, hung in a succession of galleries that have been dimmed, for the occasion, to a crepuscular murk. The dramatic darkness of the hang is more than appropriate, since the exhibition traces the deepening and darkening of Caravaggio’s art during the years he spent as a fugitive, on the run from papal justice after killing a man in a swordfight on a Roman tennis court.

The exhibition focuses on just four years of the painter’s career, from the summer of 1606, when he murdered a pimp and sometime mercenary soldier named Ranuccio Tomassoni, to the summer of 1610, when he died in suspicious circumstances while travelling back to...

Caravaggio: The Final Years at The National Gallery

27-02-2005