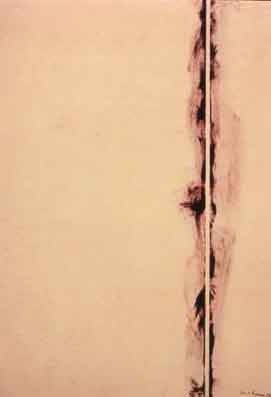

Barnett Newman painted big pictures and made correspondingly large claims about them. In the early 1960s, when quizzed by a sceptical interviewer about the significance of his art – large paintings formed from panoramic fields of ravishingly pure colour bisected by one or more tremulous, vertical stripes – Newman responded that if critics and others “could read it properly it would mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism”. By the artist’s own extreme criteria, it seems unlikely that the daunting voids of his painting will ever be fully understood. But a new exhibition at Tate Modern – the largest yet dedicated to Newman’s painting – offers audiences in this country a rare opportunity to try their own hand at “reading” the work of this solemn, unashamedly portentous but powerfully original American painter.

Few artists have taken themselves more seriously than Barnett Newman. Born in 1905, the son of first-generation Jewish immigrants from