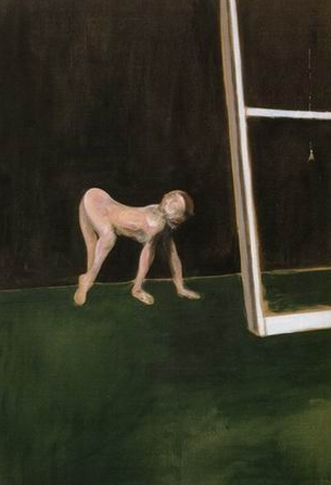

THE SOVIET General (Military Medical Services) inspected Francis Bacon's Head III, a screaming, simian ghoul painted in what looks like mud, grimaced and looked away. He had dressed up for the occasion - the official opening of Bacon's Moscow retrospective, the first granted to a living British artist since the Russian Revolution - but was finding it hard to keep up appearances. He shook his head and, medals jangling, made his way to the exit. He was reluctant to comment on what he had seen; pressed, he gave the opinion that 'Mr Bacon's paintings are evidence of a sick psyche.'

Natasha, who described herself as 'a middle-class lady', was less charitable. 'I didn't understand it, and I really didn't like it. In the speeches before they opened the doors, they said that Mr Bacon is a great painter, perhaps the greatest painter in the world. He paints such monsters, such horrors, such ugliness. I don't think it is possible for great art to be so unpleasant.' She and her companion trailed the General through the door, past the Russian flag and Union Jack which, side by side, signalled the latest exercise in glasnost.

They have a saying in Moscow: 'We Russians love foreign things, but when we want to eat well we al-ways go back to good Russian bacon.' You only need to take one trip on the Moscow underground system (price: five kopecks, about five pence) to realise why most Russians were always going to find the British Bacon hard to stomach. There, in the gigantesque statuary that lines virtually every platform, you find the sort of art that modern Muscovites have been brought up on. It is a subterranean pantheon, thronging with role models for the responsible Communist. At Revolution Square, Michelangelesque peasants, mothers, and factory workers line...