In the years after the Second World War a new form of American modern art was born. Bold and monumental, resolutely non-figurative, Abstract Expressionism seemed perfectly to express the post-war American spirit – forward-looking, risk-taking, audacious. But what is sometimes forgotten is just how suddenly and from what apparently unpromising soil Abstract Expressionism sprung into being. For much of the first half of the twentieth century, American modern art lagged far behind that of Europe. While European art was being transformed in the many crucibles of modernist experiment, most Americans – and many American artists – remained largely unaware of the work of artists such as Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso.

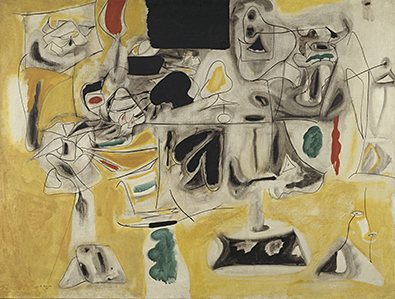

So where did the Abstract Expressionists’ brave new spirit come from? Tate Modern’s forthcoming show, “Arshile Gorky: Enigma and Nostalgia”, sets out to answer the question. Having already been seen over the winter at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the exhibition is devoted to the work of one of the unsung heroes of American modern art. An Armenian emigre, Gorky acted as a kind of transatlantic pipeline for new ideas and approaches to painting.

So where did the Abstract Expressionists’ brave new spirit come from? Tate Modern’s forthcoming show, “Arshile Gorky: Enigma and Nostalgia”, sets out to answer the question. Having already been seen over the winter at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the exhibition is devoted to the work of one of the unsung heroes of American modern art. An Armenian emigre, Gorky acted as a kind of transatlantic pipeline for new ideas and approaches to painting.

Gorky passionately believed that the successive revolutions to have swept through modern art during the first three decades of the twentieth century, principally in Paris but also in Berlin, amounted to nothing less than a second Renaissance. He set out to spread the word about it in America, and did so in a remarkably programmatic way. From the mid-1920s on, deliberately suppressing his own creative personality, he created a whole series of extraordinarily faithful homages to the major artists of the modern movement in Europe. His subjects were American, but that was all. He made Newark (of all places) look like Cezanne’s Aix-en-Provence. He turned American dancers into Picasso figures with distorted anatomies and made American...