Hans Hartung, grandfather of modern abstract painting. Or so theartist considered himself to be. Andrew Graham-Dixon remains firmly unconvinced by his claims to fame

Precedence counts for much in art. The first abstract painting will inevitably impress many people more than the third, or fifth, or ninth. But general agreement on such matters is extremely rare, and when an artist makes vociferous claims about the extent of his own originality he should always be regarded with extreme caution. "I did it first" is the perennial, plaintive cry of the unsung mediocrity. He clutches at precedence like a drowning man at a straw, because he realises that it offers him his best and perhaps only chance of an afterlife. He may not be a good artist, let alone a great one. But he knows that, if he can persuade others that he has made a significant innovation, he will be remembered and his works dutifully labelled Important and Influential.

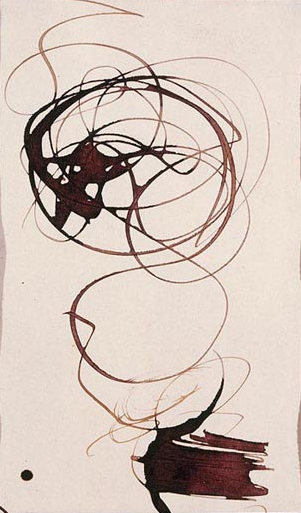

"Hans Hartung: Works on Paper 1922-56", an exhibition currently at the Tate Gallery, and the catalogue which accompanies it, written by Jennifer Mundy, seek to present Hartung as a pioneering figure in the history of 20th-century painting. Born in Leipzig, in East Germany, in 1904, Hartung was, we are to believe, "an as-toundingly original" artist, who in the period between the two World Wars invented quite new forms of lyrical and gestural abstraction. His innovations, it is suggested, crucially shaped the aesthetic attitudes of the most celebrated artists of the 1950s, including the painters of the New York School, who are mildly chastised for failing to acknowledge him. The exhibition, held in the somewhat unappealing basement galleries of the Tate, is a sparsely attended and quiet event, but these are fairly loud claims.

No secret is made of the fact...