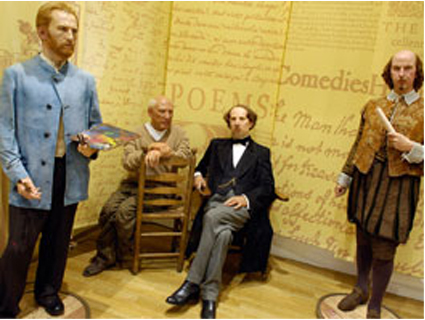

Andrew Graham-Dixon visits 'Britain's most popular sculpture gallery'

WHEN MADAME Tussaud published the first catalogue to her waxworks, back in the early nineteenth century, she expressed the hope that the figures displayed would 'convey to the minds of young Persons much biographical knowledge - a branch of education universally allowed to be of the highest importance.' Not all of the eminent Victorians who flocked to Madame Tussaud's were convinced. Charles Dickens, a frequent visitor, conceded that by the 1850s the place had become 'something more than an exhibition . . . it is an institution,' but still had his doubts about its claims to educate and enlighten. 'What can be said of the young man from the provinces,' he wondered, 'who, with red and beefy neck, gazes up at 'The Death of Marat' while consuming an underdone pork pie?'

You will still find 'The Death of Marat' if you visit Madame Tussaud's today, in 'The Chamber of Horrors'. These days, the young man gazing up at it is more likely to be an American tourist from the Midwest; if he's eating anything, it is probably a soggy Big Mac. But Dickens' original question still holds good: what can be said of him, and the thousands like him who, year in, year out, make their pilgrimage to the cathedral of wax on the Marylebone Road?

Madame Tussaud's is an enigma, an apparent anachronism which has, somehow, managed to retain its grip on the popular imagination. What is it that has enabled this particular nineteenth century institution to survive and prosper into modern times, while virtually every other species of mass-appeal visual art of the period - the panorama, for example, which pulled them in in their thousands in the Victorian era - has been killed off by the competing attractions of...