THE FIRST British retrospective of Georgia O'Keeffe's paintings, which opened at the Hayward Gallery last week, resoundingly confirms her genius, although not perhaps in the way that she herself might have wished. This exhibition reveals that O'Keeffe must have had an amazing gift for self-publicisation; an immense talent for convincing others of her talent; an absolute mastery of the art of persuasion. Because it also reveals that the most famous female American artist of the 20th century was, quite simply, not very good.

O'Keeffe emerges from this show as a mediocrity who managed to turn herself, partly through force of will, partly through sheer luck, into an icon of modern American culture. She was mediocre in the right way, and at the right time, to be taken far more seriously than her art warranted. But it is just possible that O'Keeffe may finally, a decade after her death at the ripe age of 99, have run out of luck. And it may be that the forces which have been so largely responsible for promoting her to a much higher place in modern art's pantheon than she deserves - those forces being, primarily, a certain kind of American jingoism and a certain kind of misguidedly defensive feminism - can no longer shield her work from plain, honest scrutiny of its defects. Critics, curators, artists and the rest of the art world's opinion-makers have been having their doubts about O'Keeffe for some time now, but those doubts have mostly been expressed quietly, privately, like irreverent remarks whispered in church. It is about time they were spoken out loud.

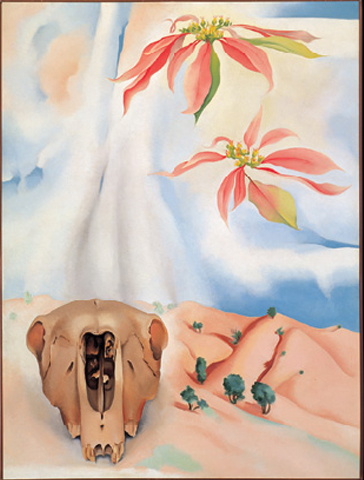

For the benefit of those who may be unfamiliar with it, the traditional, much-parroted argument for O'Keeffe as A Major American Modern Artist may be worth repeating one more time. It goes...

A legend in her own landscape

13-04-1993