Painters are often reluctant to discuss their own work and they have every reason to be cautious. Anything said may be taken down and used in evidence; one chance remark, expanded upon by a critic or art historian with sufficient eloquence and determination, may colour interpretation of an artist's oeuvre for generations.

Paul Cezanne's statement, that he sought ''to re-do Poussin over again after nature'', is one of the more famous examples of the phenomenon. Taken up by commentators such as Maurice Denis (''Cezanne is the Poussin of Impressionism'') and Roger Fry (''How much nearer Cezanne was to Poussin than to the Salon d'Automne''), Cezanne's comment has contributed to his own reputation as the great classicising painter of his age, the advocate of a return to the values of the seventeenth-century heroic landscape tradition. His few words have also fostered the notion of Poussin as a modern avant la lettre, a painter whose precise, geometrical compositions anticipate not only those of Cezanne but presage, too, the innovations of twentieth-century abstraction.

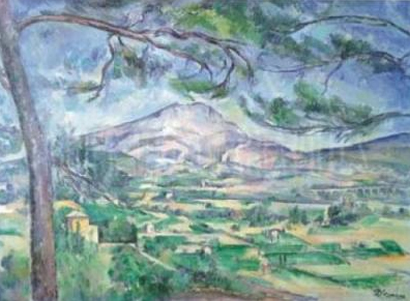

Cezanne's comment has, also, provided the pretext for ''Cezanne and Poussin: The Classical Vision of Landscape'' at the National Gallery of Scotland, the most ambitious Edinburgh Festival exhibition for years. Juxtaposing a number of major landscapes by Poussin and Cezanne, in a way that is rarely permitted by the predominantly chronological disposition of the world's great permanent collections, it offers a chance to gauge the validity of one of the more influential received opinions in modern aesthetic thought.

Curator Richard Verdi argues that his display demonstrates ''two artists' search for the most eternal qualities in nature''. But the notion of Poussin and Cezanne as a pair of kindred souls communing across the centuries comes to look suspiciously like one of those attractive simplifications whose credibility depends on the suppression of...