From underrated to overrated? Andrew Graham-Dixon on the work of David Bomberg

WHEN DAVID Bomberg died in 1957 he was, in the words of his biographer Richard Cork, "a tragically neglected artist." Thirty years later, he is being widely touted as the greatest British painter of the century. The large Bomberg retrospective currently at the Tate an institution that ignored the artist when he was alive is accompanied by no fewer than four spin-off shows in the commercial sector. "Time," to quote Tom Phillips, "is a great dealer."

Back in 1914 as one of the student rebels who prompted the Slade's tutor Henry Tonks to threaten resignation "if this talk of cubism doesn't cease" the young Bomberg seemed firmly on course for fame and fortune. It was a time of bold words and radical gestures: Roger Fry's "Art-Quake", the exhibition devoted to "Manet and the Post-Impressionists"; Clive Bell's warcry "The battle is won: we all agree, now, that any form in which an artist can express himself is legitimate."

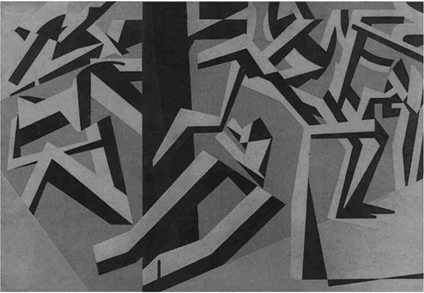

Bomberg, the slum-born son of Jewish immigrants from Poland, responded with brio. According to a childhood friend, "He wanted to dynamite the whole of British painting." Bomberg's dynamite came in the form of abstraction. "I APPEAL to a Sense of Form," he screeched in the catalogue to his 1914 show at the Chenil Gallery. His inappropriately titled Island of Joy (a Slade competition picture of 1912) arranges hordes of embattled figures in frieze-like formations. What is being fought, here, is a battle of styles. In ascending degrees of abstraction, you go from recognisably flesh-and-blood figures, at the bottom, to paperchain cut-outs at the top ideograms of people appealing to that "Sense of Form".

Bomberg's 1912 Vision of Ezekiel translates Judaic legend into an orgy of celebrating stick-people. Choosing Ezekiel's vision of...