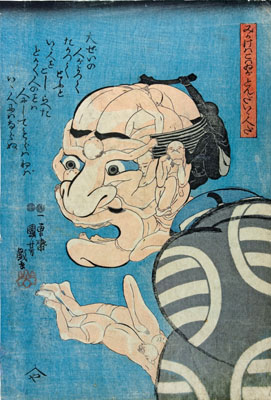

Together with Hokusai and Hiroshige, Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) was one of the great masters of the “floating world”, or Ukiyo-e, school of Japanese art. He lived and worked all his life in Edo, now Tokyo, which was at the time the largest city in the world, with a population of a million. His art was vivid and vital, less graceful than that of his rivals, but possessed by a writhing, paroxysmal energy and exuberance. He specialised in sexy sinuous women, tattooed heroes and colourfully weird demons. His shape-shifting, metamorphic monsters are in a class of their own. He dreamed of horned ghosts and giant skeletons with staring eyes. He dredged up huge sea creatures from hidden depths of fantasy.

Kuniyoshi produced affordable art for the man in the street. His prints were aimed squarely at “the townspeople”, as they were known – meaning artisans and merchants, in the old Confucian hierarchy of Japanese society. But Kuniyoshi’s works were also regarded as a guilty pleasure by the upper classes. Those at the very top of the tree of Edo’s vibrant society, the samurai, bought them by the dozen. His raucous, spectacular, populist art is the direct ancestor of modern Japan’s most vital tradition of popular cartooning, Manga. Such was his widespread appeal that one of his most popular series of woodblock prints, “Biographies of Loyal and Righteous Samurai”, released in 1847, sold a staggering 408,000 sheets. A case can be made for Kuniyoshi as the single best-selling popular artist of the entire nineteenth century, East or West.

Despite his fame, and despite the compelling brilliance and surrealistic strangeness of his work, there has been no major exhibition of Kuniyoshi’s woodblock prints in Britain for nearly 50 years. Now that situation has been put to rights by the Royal Academy, where a wonderfully...

Kuniyoshi produced affordable art for the man in the street. His prints were aimed squarely at “the townspeople”, as they were known – meaning artisans and merchants, in the old Confucian hierarchy of Japanese society. But Kuniyoshi’s works were also regarded as a guilty pleasure by the upper classes. Those at the very top of the tree of Edo’s vibrant society, the samurai, bought them by the dozen. His raucous, spectacular, populist art is the direct ancestor of modern Japan’s most vital tradition of popular cartooning, Manga. Such was his widespread appeal that one of his most popular series of woodblock prints, “Biographies of Loyal and Righteous Samurai”, released in 1847, sold a staggering 408,000 sheets. A case can be made for Kuniyoshi as the single best-selling popular artist of the entire nineteenth century, East or West.

Despite his fame, and despite the compelling brilliance and surrealistic strangeness of his work, there has been no major exhibition of Kuniyoshi’s woodblock prints in Britain for nearly 50 years. Now that situation has been put to rights by the Royal Academy, where a wonderfully...