Andrew Graham-Dixon on Michael Craig-Martin's retrospective show at the Whitechapel Gallery

It is often said that too much art is experienced at secondhand. Mass reproduction has built Malraux's 'Museum Without Walls', a place where it is all too easy to forget that the work of art is a unique object for which there can be no true substitute. But there is one area of art where secondary experience, whether de-scription or reproduction, can be preferable to witnessing the thing itself. Art history has called it Conceptualism.

Most histories of conceptual art will mention, for instance, Piero Manzoni's upside-down plinth placed in a sculpture park in West Germany - the joke being, in this case, the artist's tongue-in- cheek designation of the whole world as his sculpture - but who would ever go out of their way to see it? The idea is enough. Since the conceptual art object exists to relay a concept, to play second fiddle to the idea that it embodies, it has always occupied a somewhat uneasy position. It is the preamble to its own punchline, so once you have 'got it' you are left staring at an object that has engineered its own obsolescence - the boring bit of the joke preserved, so to speak, in perpetuity.

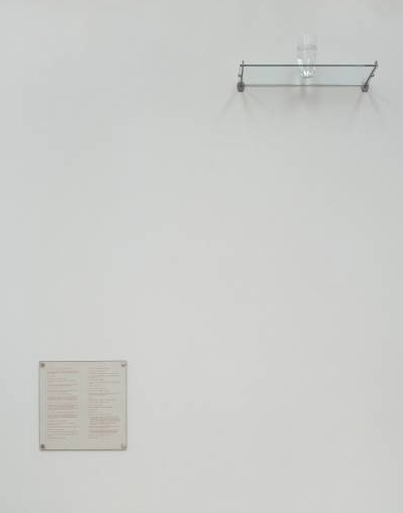

The Whitechapel Art Gallery's invigorating retrospective of Michael Craig-Martin's work turns out to be an exception to the rule. Take An Oak Tree, his best known work, which dates back to the headily concep-tual days of 1973. It is the first work you see on entry, a fabled but little seen conceptualist landmark (owned by the National Gallery of Australia), the archetypal art-object-as- idea: a glass of water on a glass shelf, no more than that, accompanied by a text in which the artist asserts that what you are...