Andrew Graham-Dixon follows the trail of British Surrealism to Leeds and and dials D for Dali.

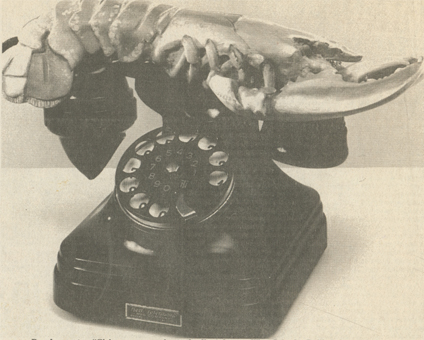

SALVADOR Dali's Lobster Telephone is the same as any normal telephone, with one additional (and non-British Telecom approved) feature — it has the shocking pink body of a lobster draped along its receiver. Dali has placed the lobster's tail, and thus its sexual parts, directly over the mouthpiece. By invit-ing the user of his telephone to engage in obscene congress with a crustacean, Dali gave new meaning to the dirty phone call.

Lobster Telephone is currently on show in "Surrealism in Britain in the Thirties", a large exhibition at Leeds City Art Galleries. Dali's sculpture (for want of a better word) dates from 1936; in the same year, Surrealism officially arrived in Britain, with the London opening of the International Surrealist Exhibition. Containing work by Ernst, Picasso, Miró, Giacometti and other lu-minaries of the movement, it failed to amuse the British press (never noted for its willingness to embrace the artistic avant-garde). "Poor jokes, pointless in-delicacies and relics of an outworn romanticism", thundered the Daily Telegraph's art critic; his colleagues frothed at the mouth in unison. The British, it seems, were not ready for the Surrealists.

Or were they? "Surrealism in Britain in the Thirties", according to its organisers, has two chief purposes. The first is to celebrate the fiftieth anniver-sary of the International Surrealist Ex-hibition in London — thirty-four of the original 390 exhibits are on view at Leeds. The second is to demonstrate that Britain was eminently ready for, and responsive to, the challenge of Sur¬realist art Our art critics may have been reactionary, but our artists were pro-gressive. The organisers argue the case for a significant school of British Surre-alists.

Unfortunately their exhibition fails on both counts. Tidily organised into thirteen...

The world's your lobster

27-10-1986