The British Museum’s main exhibition of the moment, “Fra Angelico to Leonardo: Italian Renaissance Drawings”, triumphantly reveals the vital role played by sketches and studies in the development of new ways of seeing and thinking across fifteenth-century Italy. Many of the innovations that it charts, such as the discovery of mathematically calculated perspective, or the meticulous scientific studies of Leonardo da Vinci, were only enabled by developments in technology that made paper cheaply available for the first time. Without mass-manufactured paper, certain types of thought and experiment were simply impossible, and the same holds true for the spread of literacy and the rise of the readily available book: the new papermaking technology of the Renaissance also acted as a catalyst for the invention of printing, developed by Gutenberg in the middle years of the fifteenth century.

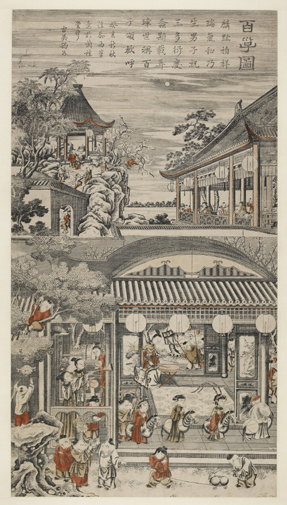

A rather smaller and somewhat less heralded exhibition at the British Museum, which opened recently in its Prints and Drawings Department, quietly sets such cultural achievements of western Europe in a global context. “The Printed Image in China”, a exhibition drawn from the entire range of the museum’s collection of Chinese prints, serves as a reminder that mass-manufactured paper and indeed printmaking had been developed in Asia almost a thousand years earlier. The show opens with what has been called the earliest extant dated woodblock print in the history of the world, the frontispiece to the so-called Diamond Sutra. Commissioned in 868, it is an image of startling intricacy which shows the Buddha, cross-legged and calmly impassive, sharing pearls of wisdom with a gnarled disciple who kneels before him in supplication, as all manner of fierce beasts and divine beings look on. The image is so rich in detail and so refined in technique that it evidently represents an already mature tradition of image-making,...