In Paris they have a grand new Renaissance sculpture gallery, refurbished by the state. In Britain, we are still managing to make a high art of philistinism, says Andrew Graham-Dixon

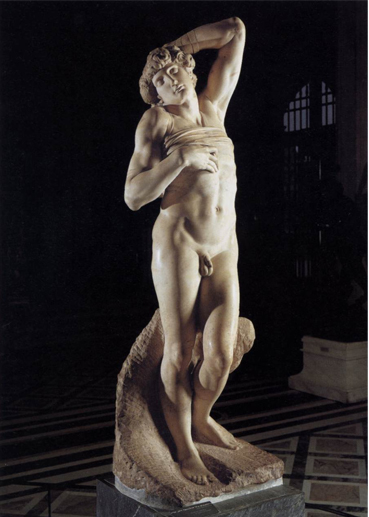

The opening of the remodelled Renaissance sculpture galleries in the Louvre last week sees the long-awaited release, from the sad obscurity of storeroom and study gallery, of some of the greatest works of art ever made in the West. Michelangelo's Dying Slave, the most haunting and sensual of all the nude figures he carved for his ill-fated tomb of Pope Julius II; Benvenuto Cellini's strange, sexy Nymph of Fontainebleau; the alabaster Annunciate by Tilman Riemenschneider, the finest sculptor of the German Renaissance; Adriaan de Vries's turbulent Mercury and Psyche, one of the masterpieces of Prague Mannerism - the new display aims to do these and many other works subtle and unostentatious justice. The opening of these galleries is a cause for celebration. It is also, if you happen to be British, peculiarly shaming.

The greatest existing collection of Renaissance sculpture outside Italy is not, in fact, the one that has just been so reverently redisplayed in Paris. It is to be found at the English-speaking end of the Channel tunnel, in a suite of dingy galleries at the back of the Victoria and Albert Museum. These rooms, some of the least-visited in the museum, contain, among other things, nine sculptures by Donatello, the Cellini Madonna, Bernini's Neptune and Triton and Giambologna's Samson Slaying a Philistine. The contrast between the Louvre's new galleries and the V&A's ill-lit corridor, filled with masterpieces so neglected that the vast majority of the British public is entirely unaware of their existence, is (to say the least) instructive.

During the last decade, the French state has spent approximately pounds 800m on making improvements to...