Paris has taken Francis Bacon as one of its own, a European painter with a vision of the uncertainties and fragmentation of the twentieth century, says Andrew Graham-Dixon

The Francis Bacon retrospective, which opened a fortnight ago at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, has been attracting approximately 5,000 visitors each day. That is a remarkable figure. Picasso and Matisse apart, it is hard to think of another 20th-century artist capable of drawing such crowds. It is impossible to think of another British 20th-century artist capable of doing so.

As far as the French are concerned, we are to understand that Bacon is not British at all, but European. According to Jean-Jacques Aillagon, the president of the Pompidou Centre, he is one of the quintessentially European artists of modern times. Indeed, Aillagon adds, the exhibition may be counted upon to reveal the "profonde Europeanite" - the profound Europeanness - of his painting. It is very unusual for the French to consider a British artist as one of them, as part of the mainstream, in quite this way.

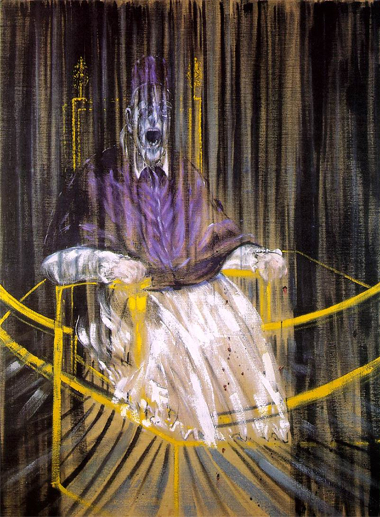

The desire to recruit Bacon as a "European" is not entirely perverse because, at the level of its technique, Bacon's art does speak long and lovingly about the art of the Italian, Spanish and Dutch masters he admired (above all Titian, Velzquez and Rembrandt). Yet the Pompidou exhibition and its popularity surely says as much about the the times in which we live as it does about Bacon's art.

The readiness or the desire to see this difficult, refractory boundlessly vital individual as an emblematic trans-national European figure may be symptomatic of something else; part of a broader quest for some binding sense of European identify, perhaps. But there is a paradox here, because Bacon's grand subject is the troubled...