William Blake’s annotations to his copy of Sir Joshua Reynolds’ Discourses on Art are among the most vigorous expressions of disgust in the history of British art. In these frenetic scribblings, the visionary Romantic outsider screamed his rage at the ghost of the Royal Academy’s first President. On the title page of the book, next to Reynolds’ name, Blake wrote bluntly that “This Man was Hired to Depress Art.” Then he warmed to his task: “Having spent the vigour my Youth & Genius under the Oppression of Sr Joshua & his Gang of Cunning Hired Knaves Without Employment & as much as could possibly be Without Bread, The Reader must Expect to Read in all my Remarks on these Books Nothing but Indignation & Resentment. While Sr Joshua was rolling in Riches, Barry was Poor & Unemploy’d except by his own Energy; Mortimer was call’d a Madman, & only Portrait Painting applauded by the Rich & Great ... Fuseli, Indignant, almost hid himself. I am hid.”

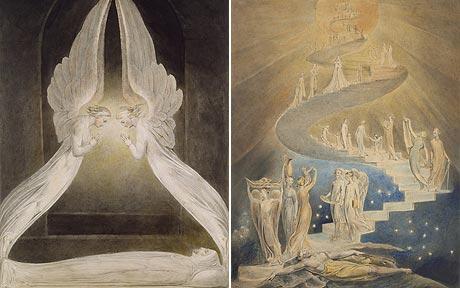

Blake hated Reynolds for encouraging the British aristocracy in its woeful attachment to the lesser genre of portraiture. His own counter-cultural heroes were men such as John Hamilton Mortimer, Henry Fuseli and James Barry, who had dedicated themselves to the production of grand narrative history paintings despite an almost total lack of patronage for such work in the British Isles. The diminutive, Swiss-born Fuseli had nearly ruined himself by opening his so-called “Milton Gallery” in London, full of unmarketable mannerist depictions of scenes from Paradise Lost. Barry had toiled unpaid, for seven whole years, on four monumental canvases for the Royal Society of Arts illustrating “the progress of human civilisation” – a group of magnificently weird pictures that can still be seen, today, in the lecture room of the RSA’s headquarters, just off...

Blake hated Reynolds for encouraging the British aristocracy in its woeful attachment to the lesser genre of portraiture. His own counter-cultural heroes were men such as John Hamilton Mortimer, Henry Fuseli and James Barry, who had dedicated themselves to the production of grand narrative history paintings despite an almost total lack of patronage for such work in the British Isles. The diminutive, Swiss-born Fuseli had nearly ruined himself by opening his so-called “Milton Gallery” in London, full of unmarketable mannerist depictions of scenes from Paradise Lost. Barry had toiled unpaid, for seven whole years, on four monumental canvases for the Royal Society of Arts illustrating “the progress of human civilisation” – a group of magnificently weird pictures that can still be seen, today, in the lecture room of the RSA’s headquarters, just off...