Andrew Graham-Dixon reviews a retrospective of the work of Francis Picabia at the Royal Scotish Academy

FRANCIS Picabia was never your common or garden modernist revolutionary. He was ex-tremely rich, for one thing, the son of a Cuban-born Spanish aristocrat, and irritated most of his contemporaries in Dada and Surrealist circles by leading a dual existence, artistic anarchist and big-spending socialite rolled into one. Picabia collected fast cars (he is said to have owned over 100, including several Hispano-Suizas and a 40hp Rolls-Royce) and faster women with an almost absurd, Don Juan-like profligacy, which was mir¬rored in the free-wheeling vagrancy of his art.

Always a natty dresser, he once remarked that "If you want to have clean ideas, change them as often as your shirts." "Francis Picabia, 1879-1953", the main exhibition at this year's Edin¬burgh festival, is bewilderingly varied — a series of quick-change routines so frequent and radical as to make it scarcely credible as a one-man show.

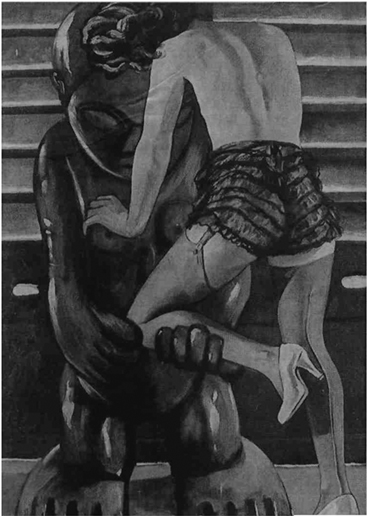

Picabia's first major change of direction seems to have been triggered by his trip, with Marcel Duchamp, to New York in 1913. The only pre-New York painting in Edinburgh is La Source, a Cubo-Futurist orgy of forms, half human, half mechanical. Sex and machines always fascinated Picabia; in America he was roused to combine his twin concerns in a more radical, less deriva¬tive fashion. In New York, he later wrote, "it flashed upon me that the genius of the modern world is in machinery and that through machin¬ery art ought to find a most vivid expression."

Picabia, a confirmed nihilist, used machine im-agery to express his complete lack of faith in mankind's moral or spiritual dimensions. His work came to consist, largely, of crude mechani-cal diagrams with overt sexual connotations: do-ing away with fine art, he abandoned painting as such for...