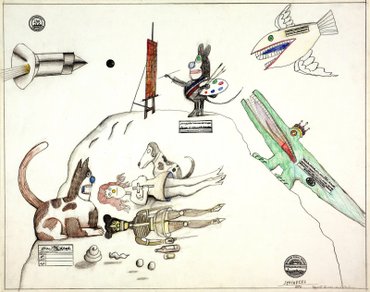

It is the summer of 1970 and Saul Steinberg, principal cartoonist at the New Yorker, is thinking dark thoughts. The Artist is the title of his latest drawing, an acerbic meditation on what it might mean to be “a painter of modern life” – to borrow Baudelaire’s nineteenth-century phrase – in late twentieth-century America. The artist in question turns out to be a Mickey Mouse figure. He stands on the summit of a barren hillock, Steinberg’s mocking symbol of a modern Parnassus, with his precariously perched easel before him. Meanwhile, all hell is breaking loose. A cruise missile heads straight for the painter’s canvas. A great fanged bird dive-bombs him from another quarter of the sky, while a crocodile, jaws gaping, creeps up on him from behind. Lower down the hill, a topless floozie clutching a crucifix lies comatose next to an emaciated Minnie Mouse in fishnets. Empty whisky bottle beside her, stiletto in hand, Minnie might be contemplating suicide but lacks the energy to do the deed. A solemn dog and anguished cartoon cat constitute a chorus of dismay.

This much is clear – the drawing is no disguised portrait of its creator, because the Mickey Mouse painter is the very image of the artist Steinberg was determined not to become. He is decorated with a tricolour sash, indicating that he has sold his soul for honours. He is oblivious to the chaos surrounding him, indifferent to sex and drugs. He is altogether unaware that he is being threatened by the weapons of mass destruction, and stalked by the dark forces of worldly power (the crocodile, wearing a crown, was Steinberg’s code for corrupt, nepotistic Washington). The image on his canvas, set at a tantalisingly oblique angle to the viewer, is a mesh of coloured lines –...