Curved space in plastic and nylon: Andrew Graham-Dixon visits Naum Gabo: Sixty Years of Constructivism at the Tate Gallery

WHEN HE was twenty one Naum Gabo went to a lecture on Einstein's Theory of Relativity. "I grasped the idea," he said later, "though I couldn't say exactly what it was about. But there was an elation in the air." An understanding of E=mc2 seems an unlikely starting point for a career in sculpture — but the Tate's magnificent Gabo retrospective shows just how successfully he translated his enthusiasm for the scientific revolutions of the early twentieth century into visual form.

Confronted by Gabo's science fiction constructions in perspex, glass or metal, the temptation to turn to the show's heavyweight catalogue for explanation is irresistible. There you learn, for example, that Construction in Space: Two Cones — which gummily glues two funnels of celluloid end-to-end and weaves curving lines of black around them — proves that Gabo "was seeking a way to indicate his perceptions that space is both continuous and curved, a concept undoubtedly influenced by Einstein's notion of spatial curvature."

All this begs a pressing question: do you need a doctorate in nuclear physics to appreciate Gabo's sculpture? His constructions certainly fail as scientific models: few visitors to the Tate will find the scales falling from their eyes, and exit with cries of "eurekal — so that's what Einstein was on about." But neither will they leave groaning with frustration at Gabo's work, which turns out to be a lot less obscure than many of his commentators suggest.

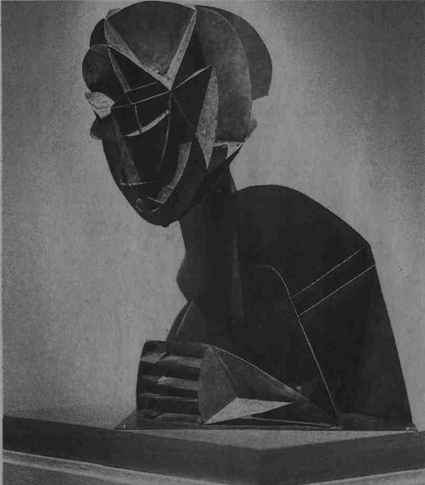

The exhibition opens with his powerful early figurative sculptures, the Constructed Heads: looming female busts in latticed metal, wood, or ivory that interpret human form as a honeycomb of planes and voids. Clearly influenced by the Parisian avant-garde, Gabo's heads signal...

Particle sculpture

14-02-1987