Matisse once said that ''whoever wishes to devote himself to painting should begin by cutting out his own tongue''. A fairly radical recommendation - suggesting, among other things, that Van Gogh took the right approach to the wrong part of his anatomy - but Matisse didn't really mean it. What he was driving at, presumably, was the fundamental incompatibility of painting and language. ''Painting is its own language,'' as Francis Bacon has put it. ''When you try to talk about it, it's like an inferior translation.''

But anyone who spends much time looking at pictures will have noticed that most people continue to feel the need for some form of verbal explanation. It is evident in what might be called the museum two-step: walk up to painting; duck sideways to check title. The need can be denied - as Lucian Freud attempted to do when he hung his selection of National Gallery paintings, in the ''Artist's Eye'' series, without captions - but it cannot be stifled.

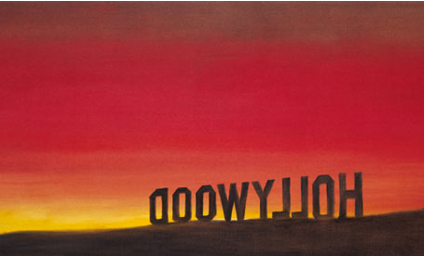

A new book about a dead artist (Turner) and two new exhibitions of work by living ones (Richard Long and Edward Ruscha) suggest the close - if occasionally uneasy - relationship that has always existed be-tween the image and the word. Artists don't always follow Matisse's advice, and the results can be interest-ing.

Andrew Wilton's Painting and Poetry (Tate Gallery Publications, pounds 14.95) demonstrates Turner's obsessive keenness to provide his pictures with literary glosses. This is clear, not just in the elaborate titles Turner devised for his pictures, but also in the ponderous and fatalistic poem on which he toiled for years (but never managed to finish), The Fallacies of Hope. Turner's verse - snatches of which he insisted on in-cluding in the catalogue entries for his pictures - is turgid at best, a...