This past year will largely be remembered for a number of remarkable exhibitions, especially, perhaps, Richard Kendall's brilliant "Late Degas" at the National Gallery, and (at the same institution) Christopher Brown's exhilarating show "Rubens's Landscapes". The Sainsbury Wing's basement galleries can sometimes seem depressingly sepulchral, but on these two occasions they seemed intimate instead - appropriate for works like Degas's late pastels or Rubens's landscapes, which are fascinating partly because they are works evidently charged with so much personal meaning for the artists who created them. The exhibitions were, of course, totally different from one another, but nevertheless the sense of having stumbled into some private chamber of a great artist's imagination was overpoweringly strong in each case.

This type of relatively small but highly focused exhibition has prospered in recent years, especially at the National Gallery - although the credit for establishing it in this country as a credible alternative to the block-buster should perhaps go to the Tate Gallery's director, Nicholas Serota, who put on a number of smaller shows (eg "Max Beckmann's Triptychs", "Late Leger" and others) during his time at the Whitechapel Gallery in the 1980s.

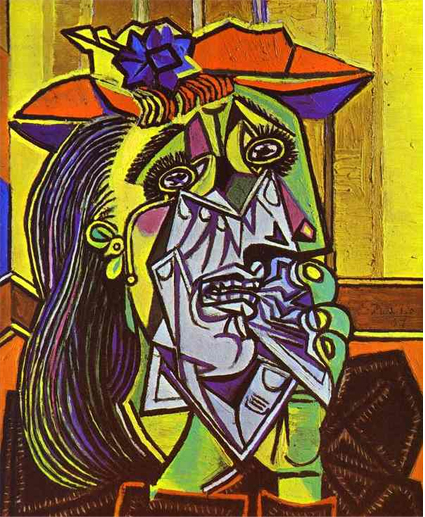

Leaving aside the Tate's own enormous and inevitably popular Cezanne exhibition, it has not been a great year for the huge crowd-pulling exhibition. "Picasso and Portraiture", at the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Grand Palais in Paris, was symptomatic - this was a somewhat disappointing and opportunistic event, a nakedly biographical exhibition that turned out to be considerably less revealing than the second volume in John Richardson's ongoing biography of the artist, which was clearly the inspiration for it.

The late 20th century's fascination with Picasso seems to be short-circuiting on a circular argument: his art is fascinating because it reveals him to...

Last of the great showstoppers?

26-12-1996