When Jackson Pollock posed in front of his ancient Model T Ford for photographer Hans Namuth in 1951 he was playing a part. He was acting out the role of the brusque bluecollar painter demanded by his legend (for Pollock was already by then, aged 39, one of the most celebrated painters in the world); and he was proving, in the eyes of many, that a no-nonsense American did not have to abandon his roots to succeed in the exotic occupation of Modern Artist.

The truth was more complicated than Namuth’s image suggested. For one thing, Pollock no longer drove the car pictured in the photograph, having earned more than enough from his paintings to buy himself a brand-new Cadillac convertible; for another, he had begun to doubt whether he was, after all, quite the unmitigated success his publicity told him that he was.

“Jackson Pollock” at the Tate Gallery (11 March-16 June), originally at the

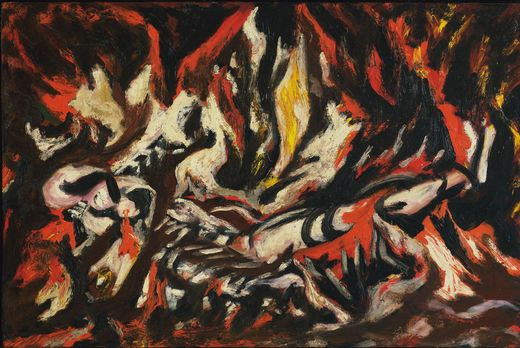

Formed from coils and loops and whorls of paint spun out across the canvas like the webs of an eccentric spider, the beauty of these works of art is...