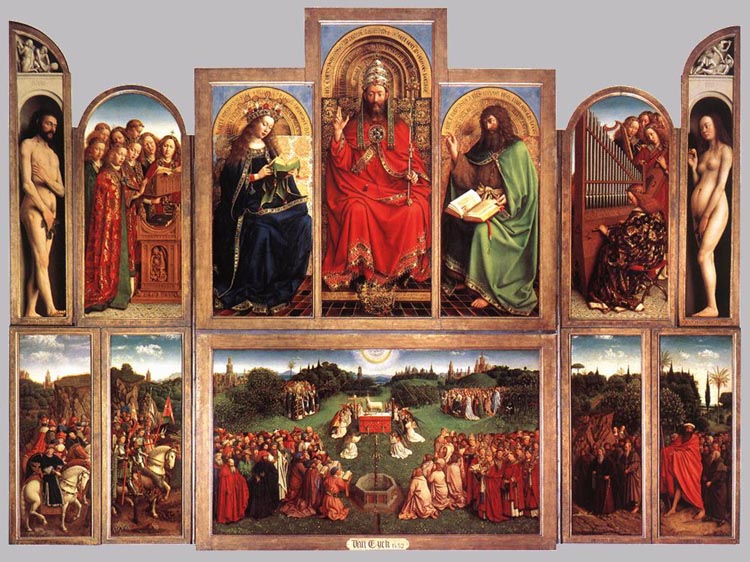

On Remembrance Sunday, this week’s painting is The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb. The hardy survivor of two World Wars, it owes its remarkably intact condition to the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.

The Ghent altarpiece, as it is also known, is in the church for which it was commissioned more than five and a half centuries ago. This can give the misleading impression that Hubert and Jan van Eyck’s masterpiece has led a cloistered existence. But it is hard to think of a painting that has lived more dangerously. Over the course of its life it has been split up, sold off, reassembled, hidden away and taken prisoner of war by the Nazis, who stashed it at the bottom of an Austrian salt-mine at Altaussee.

Arguably the single most influential work of the Northern Renaissance, the Ghent altarpiece was one of the first pictures fully to exploit the relatively untried medium of oil paint. The Van Eycks taught a whole generation of artists how oils could be used to conjure flesh and blood, to imitate man-made fabrics, the natural world and the play of light and shade, with unprecedented fidelity. The Adoration of the Lamb was their demonstration piece. Its very renown led to many of the vicissitudes that it has suffered.

The altarpiece’s trials began in the sixteenth century when clumsy restorers accidentally destroyed its predella, which included a lively representation of hell. Then came a virulent outburst of Protestant iconoclasm, and the painting was hidden away in the cathedral tower. The Calvinists expelled it from St Bavo’s altogether, keeping it in the town hall and attempting unsuccessfully to sell it to an agent acting on behalf of Elizabeth I.

Following the French Revolution Napoleon’s troops hauled it off to Paris, where it had a profound...

ITP 30: The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, by Hubert and Jan van Eyck

12-11-2000