On the eve of the Second World War, the art critic Eric Newton reviewed an exhibition of new paintings by Graham Sutherland. The writer was impressed but also disquieted by what he saw: “Mr Sutherland’s world is an unfinished thing, as though it had been abandoned half-way through the fifth day of creation. His shapes, for all their subtlety, are clumsy. They suggest dinosaurs and mammoths. His hills heave themselves grimly against the sky. They are stark uncomfortable monsters made of raw earth and rock.”

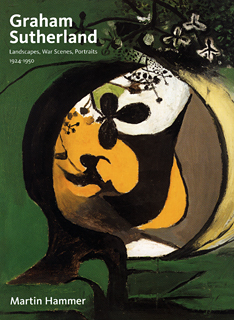

“Graham Sutherland: Landscapes, War Scenes, Portraits”, at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, is a modestly scaled but exemplary exhibition, devoted to the work of one of England’s most original and underrated twentieth-century painters. Discriminatingly selected by Martin Hammer, the exhibition seeks to rehabilitate Sutherland’s somewhat faded reputation, and does so by concentrating on the work of the first and more experimental half of his career – the pictures that he created between 1924 and 1950, before succumbing to religiosity and self-repetition.

The show opens, in midstream, with a number of the dark and metamorphic landscapes with which Sutherland, in his mid-thirties, impressed not only many of the leading critics of the day, such as Eric Newton, but also the new young director of the National Gallery, Kenneth Clark, who would prove to be a staunch, lifelong supporter. The picture’s titles are matter-of-fact. Red Tree, Sunrise between Hedges, Gorse on Sea Wall, are characteristic examples. They seem designed to set up the expectation of a narrow, anecdotal, topographically precise form of landscape painting – an expectation which the works themselves thoroughly subvert. Spiky, angular, awkward forms – shapes that resemble rocks, or fallen tree-trunks, or writhing vegetation – occupy tip-tilted abstract landscapes. Sutherland’s palette is biliously vivid, formed from reds the colour of rust or...

Graham Sutherland at the Dulwich Picture Gallery

19-06-2005