“George Catlin: American Indian Portraits” at the National Portrait Gallery.

In 1830, under the rapaciously expansionist presidency of Andrew Jackson, American Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. Native American tribes were forced ever westwards and those who resisted were killed or forcibly removed from their lands. An enterprising painter from Philadelphia called George Catlin set out to record what he believed to be a noble but vanishing race. The many hundreds of pictures that he painted, at the frontier and in the wilds, have long been prize possessions of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. A generous selection has been loaned to the National Portrait Gallery, to form an enthralling new exhibition. “George Catlin: American Indian Portraits” raises the curtain on a figure who was painter, philanthropist and showman rolled into one; and it movingly reconstructs his most ambitious project.

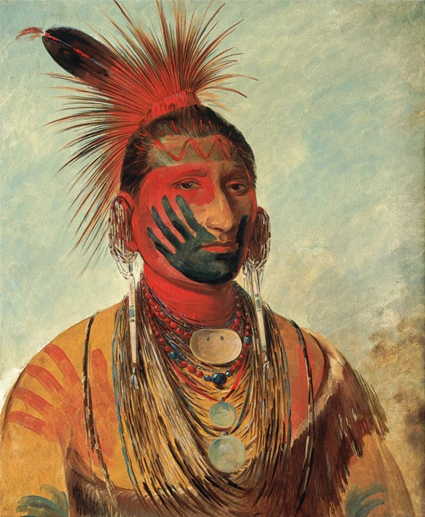

In 1832 Catlin boarded the steamboat Yellow Stone, bound for Fort Union, a trading post close to what is now the border of Montana and North Dakota. He set up a studio and painted the Blackfoot, Crows and others who traded there, warily, with the white man. He travelled to the Jefferson Barracks, Missouri, to paint captive chiefs. Black Hawk, Prominent Sac Chief is one of the most powerful American portraits of the nineteenth century: against a cursorily painted sky full of stormclouds, one of the most articulate American Indian leaders, dressed in his tribal robes and jewellery, stares into the distance with an expression of concern on his gentle, dignified, finely lined face. He might be thinking the regretful thoughts that punctuate the autobiography he dictated a year or so later: “Why did the Great Spirit ever send the whites to this island to to drive us from our homes and introduce among us poison liquors, disease and death?...