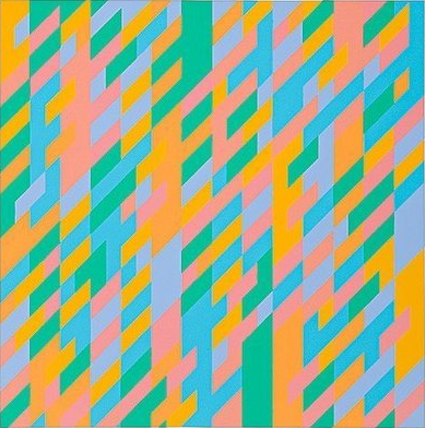

Bridget Riley does not see things in black and white. ''All artists are mixtures,'' she says. ''They are complicated. I don't think they are one simple thing.'' The remark may conceal a certain irritation since Riley, who was 60 last year, has had to work unusually long and hard to convince people of her own complexity. She is one of those artists for whom early fame may, in retrospect, prove to have been as much a handicap as an advantage. Next week sees the opening, at the Hayward Gallery, of an exhibition devoted to Riley's paintings of the last decade. But she still remains, in many people's minds, inextricably identified with the era in which she first came to prominence - someone who, along with the likes of Mary Quant and Twiggy, helped to create one of the distinctive ''looks'' of the Sixties. Riley has been remembered as a pioneer of Op Art, the creator of canvases whose weird effects - dancing dots or pulsing curves, black on white grounds, designed to induce dizziness - seemed to sum up the spirit of the times. Her disorientating paintings seemed like the visual accessories of LSD culture: psychedelia, so to speak, without the colour.

But maybe it was all a terrible mistake. People began to get her all wrong, as far as Riley is concerned, as early as 1965, when she was included in a group show called ''The Responsive Eye'' at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. ''I was terribly disappointed with the American response to my work, because at that time it seemed as though the best critical minds were over there, and I wanted to know what they really thought. Well, there was no chance: the hullabaloo knocked out all serious consideration. People complained about how...

Earning her stripes

08-09-1992