Andrew Graham-Dixon on David Machn at tne Tate, plus Hofman and Turner

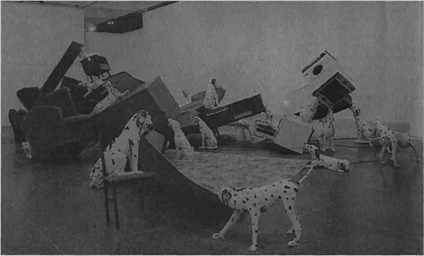

DAVID MACH has been responsible for some pretty weird sculpture in his time, but 101 Dalmatians takes the dog biscuit. It gets a room to itself at the Tate, and needs the space. A spreading mess of junk furniture, odds and ends of carpet and assorted domestic appliances tum¬bles through the gallery, like an impromptu spillage from a removal van. Mach certainly puts a lot into his work; this one includes a washing machine, a deep freeze, an electric cooker and a music centre, circa 1960. It's all there bar the kitchen sink.

That's only the mise-en-scène. Mach's obsolescent domestic items are assaulted by a pack of plaster-of-Paris Dalmatians. One, like a performing seal with a beachball, balances a washing machine on its nose. Most of the others are rather more ferocious, playing tug-of-war with carpet and chairs, coming away with mouthfuls of stuffing or emerging from fridge-freezer lairs to savage this cupboard or that coffee table.

Mach has a sense of comedy that distinguishes him from most of the other, dourly conceptual políticos currently mining the territory of installation. Like most young Scottish artists, he is no respecter of tradition; he is a confirmed iconoclast, whose work frequently points up what he perceives as the conceit of the art of the past. He has remade Henry Moore reclining figures from stacks of old magazines, artfully piled to bulge in the right places; he has jokily reconstructed the Parthenon out of car tyres. Monumental art or architecture is anathema to Mach, whose works arc almost always temporary affairs, that run for a set period of time and are then dismantled.

But for all its oddball extravagance, there is a serious side to Mach's work. If it can be...