SUSAN SONTAG once wrote that ''interpretation is the revenge of the intellect upon art'', but some art just won't be explained away. Cubism has remained relatively untouched by the herculean attempts at exegesis that it has prompted since the second decade of this century. There is still something difficult and unfathomable at its core, and while there is hardly a major artist of this century who has not in some way been influenced by it, there is still a sense in which it seems never to have been entirely understood. ''Juan Gris'', at the Whitechapel Gallery, is a beautiful puzzle of a show - a gathering of works that still have the aspect of unsolved riddles.

Posterity has simplified Gris, who joined the Cubist club late, around 1911, at a time when Braque and Picasso were creating the most hermetic and puzzling of all Cubist pictures: impenetrable, virtually abstract works from whose busily overlapping planes it is almost impossible to extract anything much like the subject of a conventional easel picture. Gris has been remembered as Apollinaire's ''demon of logic'', the artist who set himself the task of setting Cubism's shattered bones, of evolving compositions of grand stasis and calm from its fractured maelstrom of a world. But this myth of Gris turns out to be less than completely adequate.

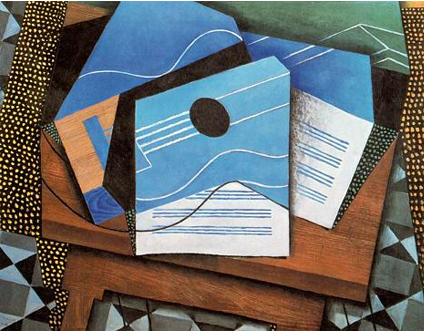

Take Gris's Guitar on a Table of 1915, one of the most seductive paintings in the present show. What the eye sees is a peculiar blend of the imagined and the real which is reflected in its style, see-sawing from the mimetically faithful to styles that self-evidently declare themselves to be mere signs for things, forms of visual code. On a table painted with high-fidelity realism lies a sheaf of papers marked with blank musical staves: a field...

Circling the square

22-09-1992