The Yongzheng Emperor sits in majesty on his throne, preserved for posterity by his court artists as Supreme Sovereign of China. His plump impassive face has been painted in fine detail, down to the last trembling whisker of his down-turned moustache. His right thumb, perfectly manicured, as delicate as a piece of porcelain, emerges from a finely decorated dark blue mitten of embroidered silk. Otherwise he deigns to reveal no flesh at all. He confronts his audience wrapped in the auspicious patternings of absolute power. Resplendent in court robes of Chinese imperial yellow, emblazoned with snarling dragons, he perches on an ornate throne which seems to float, rather than simply rest, on a carpet of dizzying geometrical design.

“China: The Three Emperors, 1662-1795”, at the Royal Academy, is a rich display of art and artefacts produced by and for the three most powerful emperors of China’s last dynasty, the Qing. The world which it evokes can seem, by turns, forbiddingly remote and unexpectedly vivid. Drawn almost exclusively from the collections of the Palace Museum in Beijing, the exhibition opens with a dazzling gallery of full-length depictions of emperors and their consorts. Here the Yongzheng Emperor is joined by his father, the Kangxi Emperor, the redoubtable warrior who first established the Qing dynasts as rulers of China; and by his son, the Qianlong Emperor, famous for connoisseurship as well as political astuteness. All have been painted according to time-honoured conventions of imperial Chinese portraiture, designed to express immutable potency. The figure is always enthroned and always posed, with fearful symmetry, so as to look straight out of the picture. But ripples of outside influence also animate the surface of these pictures. Western European art was admired by the Qing rulers of China, who not only tolerated Jesuit missionaries at their court...

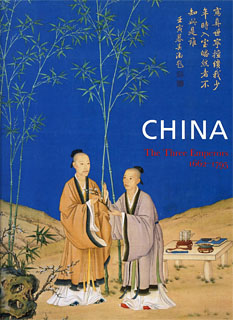

China: The Three Emperors, at the Royal Academy 2005

20-11-2005