ART / Andrew Graham-Dixon reviews the Tate Gallery's retrospective of Mark Rothko, Old Master of abstraction

WALKING INTO the first room of the Mark Rothko retrospective at the Tate, you feel as if you are in the wrong exhibition: dark ex-pressionist interiors, Hopper-like New York subway scenes, even a moody self-portrait — but not an abstract painting in sight. A room or two later, you are in familiar transcendental territory, surrounded by the looming, flowing canvases that announced Rothko's move to abstraction; hovering tiers of disembodied, as-sonant colour that float on large unframed canvases, paintings of nothing (or everything, depending on how seriously you take the spiri¬tual claims that have been advanced for his art) which have established him, less than 20 years after his death, as the undisputed Old Master of New York abstraction.

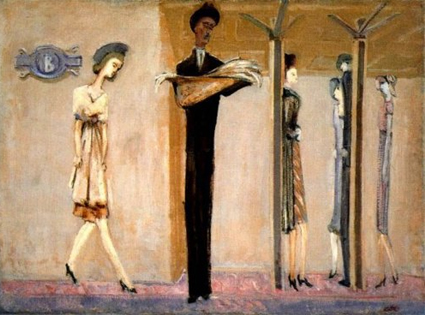

With the benefit of hindsight, Rothko's early work seems full of abstract portents, Woman Sewing painted in the mid-1930s be¬comes notable, not so much for the figure of the woman herself, bent over her task like a sinuous El Greco worshipper, as for periph-eral background details; the chair on which she sits, rendered in a single sweep of muddy ochre, or the wall behind her, a gloomy colour field in whose muted resonances it is tempting to see the late Rothko's obsession with purged, abstract surfaces. Likewise the figures in his Subway, pinched, Giacomctti-like atten¬uations, seem on the point of evanescence, leaving the artist's true concern as the articu¬lation of wall and floor, the manipulation of painting blocks of subjectless colour.

Rothko never called himself an abstract painter; as he asserted in a letter (written jointly with Adolph Gottlieb) sent to The New York Tunes in 1943, "there is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that the subject is crucial". So...