Andrew Graham-Dixon on the work of C R W Nevinson, An english English Futurist disillusioned by the Great War

WHEN FILIPPO Marinetti, chief spokesman of the Italian Futurist movement, decided to spread his gospel in England, he found a willing disciple in CRW Nevinson. In 1914, they published an 11-point denunciation of the "passéist filth" which, they believed, muddied the waters of avant-garde English art. Vital English An was against, inter alia, "the pretty-pretty, the commonplace, the soft, sweet, and mediocre, the sickly revivals of mediavalism, Aestheticism, Oscar Wilde, the Pre-Raphaelites, Neo-Primitives and Paris." It was for "an English art that is strong, vital and anti-sentimental", and ushered in the future in capital letters: "Forward! HURRAH for motors! HURRAH for speed!"

When Marinetti read his poetry at the Doré Galleries, he gave young Nevinson a large drum and had him supply the requisite sound effects — "the noise of bombardment". Months later, Nevinson — the subject of a fine exhibition at Kettle's Yard — was driving ambulances at the Front. The bombardment was real this time; posted to Dunkirk, he later recalled, "I felt I had been born in the nightmare. I had seen sights so revolting that man seldom conceives them in his mind... We could only help, and ignore shrieks, pus, gangrene and the disem-bowelled."

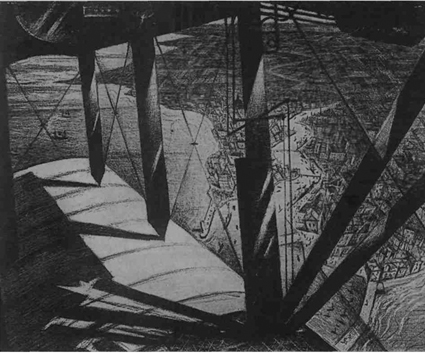

Nevinson's wartime pictures — his best work by far — do not merely document the 1914-18 conflict. They record the stages of his disillusionment with the Futurist ideal. Marinetti had celebrated the soullessness of the modern age, predicting a new utopia where individuals would be absorbed into the collective human machine. This abolition of individuality became the great theme of Nevinson's wartime art — seen, however, not as a heaven but a hell. In Returning to the Trenches, Nevinson remakes a column of...