There was a time when being an artist, in New York, was considered a noble and even heroic enterprise. Not any more. Those old notions have taken a beating during the last decade. The hot American artists of the 1980s would never have dreamed of confessing to anything as unhip as a sense of idealism. Koons, Steinbach, Bickerton: their art took its inspiration from the world of advertising; they even sounded like an advertising agency. They peddled product and made lots of money.

What would their predecessors in the modern movement, raised to believe in the sacerdotal function of the artist, have made of it all? Ad Reinhardt, for one, would not have been impressed. ''You think of an artist as a priest or a teacher,'' he once said. ''He's a better person than a businessman. I guess everybody feels that way. It's funny to have a priest with a high salary.''

But perhaps the days of priests on high salaries are numbered. A substantial proportion of the commer-cial galleries that sprang up in SoHo and Greenwich Village in the 1980s have closed or are closing, victims of the massive slump in the art market. The idea of going into art for the money now seems laughable. Reinhardt would have been pleased; and almost as a reminder of the old values of old post-war New York, the Museum of Modern Art is staging a major retrospective of his grand, solemn, withdrawn paintings. They are mementoes from a different era, when idealism was not a dirty word.

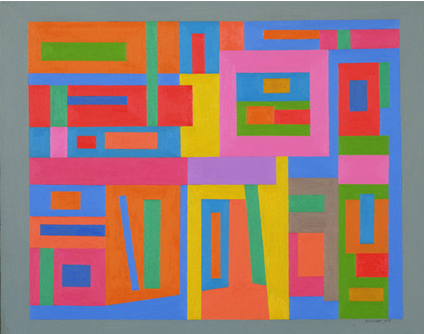

Reinhardt believed in abstraction as the one true church of modern art with a fervour unparalleled in any other major American painter. Nicknamed ''the black monk'', he was a rarity: an ascetic with a sense of hu-mour. The MOMA show opens with a sequence...